Nine Auditing Rules

All auditors receive training in the basics of planning, conducting and reporting audits. Unfortunately, this is the only training many ever receive.

Here we are going to present 9 rules or guidelines that definitely will make the audit successfully if practiced.

Rule 1

Make auditees feel like members of the audit team. Instead of using the opening line, “Don’t worry, we’re not here to audit you, we’re here to audit the system,” say something like this: “We’re doing an evaluation of the [blank] process. We’re trying to identify any weaknesses in the process or opportunities to improve it. To do that, we need your help. We’d like you to walk us through the process and explain how it works. We might need you to answer some questions or show us some of the records generated. If there is anything that doesn’t work very well or improvements you feel would make the process better, we’d like to hear about those, too. If you have any questions, please feel free to ask them. OK?”

This kind of opening statement sounds much more sincere and truly reflects the role of the auditees. It also makes them members of the audit team, which is really what they are.

Rule 2

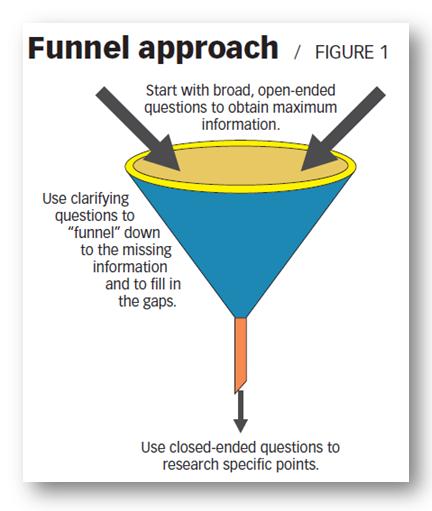

Start the evaluation by asking general, open-ended questions, then use clarifying questions to fill in the gaps. There are three primary types of questions an auditor can ask during an interview: open-ended, closed-ended and clarifying.

Open-ended questions have no right or wrong answers. Auditees are free to respond to the question to a level and depth with which they feel comfortable. The auditor gets significantly more information from an open-ended question than from a closed-ended one. Also, because there are no right or wrong answers, auditees are generally more comfortable with open-ended questions, assuming the questions address a topic or process with which they are familiar. Closed-ended questions elicit yes-no responses or specific right-wrong answers. For example, “Is there a communications log?” will bring either a yes or a no response. Likewise, “How often are environmental regulations updated?” will result in a single response such as “quarterly,” “annually” or even “we don’t.” Only one of these is likely to be correct, so the auditee has a greater chance of “crashing and burning” when answering a closed-ended question.

Clarifying questions are designed to fill in the gaps. If the auditee’s initial response revealed nothing about feasibility reviews, the auditor would ask a clarifying question: “I didn’t hear you mention anything about feasibility reviews. Can you explain when they are done and who does them?” The clarifying question is used to fill in the gaps or funnel down to the missing (or suspect) information. When used in this manner, open-ended, closed-ended and clarifying questions form a strategy for conducting interviews we call the funnel approach, which is illustrated in Figure 1. To summarize, the use of the funnel approach leads to an efficient audit that covers the maximum amount in the least time. It is also safer to auditees and allows them to warm up in the interview.

Rule 3

Be an active listener. The importance of active listening cannot be overstated. An often quoted rule of thumb is that auditors should spend only 10% of their time talking and 90% listening during an audit.

An alarming statistic provided by research is that up to 70% of all communications are misunderstood. While many of these miscommunications might have no significant impact during routine interactions, a miscommunication during an audit can have devastating effects on both auditee and auditor credibility. Simply stated, auditors must be active listeners. Active listening involves hearing not only the words used by the speaker, but also the way the words are used, and observing the nonverbal cues. The words themselves convey only a part of the message, sometimes less than 10%, while the nonverbal cues, such as facial expressions, body language and movements; possibly contain more than 60% of the overall communication. This is especially true when trying to gauge the truthfulness of a response.

Rule 4

Never let the auditee pick the samples. Assume you’ve been assigned to audit the purchasing process, and one of the requirements states that any receipt of nonconforming material will result in a supplier corrective action request (SCAR) being issued to the supplier, with a copy of the SCAR and response being placed in the supplier’s history file. How would you verify that the SCARs are being issued as required?

Many auditors would ask the purchasing manager for examples of a supplier providing nonconforming product. This allows the auditee to select the samples, which is never a good way to find the weaknesses.

A better strategy would be to stop by the receiving department on the way to purchasing and note several instances of incoming product problems using the receiving department records. When the auditor wants to verify this requirement during the purchasing-manager interview, he or she can then specifically ask to see the history files for the suppliers noted during this visit to the receiving department.

Auditors should examine each question on their checklists and ask themselves, “How will I verify the auditee’s response? Do I know what to ask for and how I will choose the samples?” If the answer isn’t evident, the auditor should develop a verification strategy and add it to the checklist.

Rule 5

Always try to identify any real effects of your findings, using dollar values when available. One of the things that sets the superstar auditors apart from their counterparts is their ability to tie findings to real consequences. They have the ability to transform the finding from a technical violation into a problem that is affecting the organization. They get management’s attention. They also get management’s support.

Rule 6

Always confirm your findings with the auditee. Before leaving, auditors should always share their findings with auditees. This is critical when you think you have found a nonconformance. Sharing the finding avoids invalid findings generated because of miscommunication. Recall that 70% of all communications are misunderstood. A well-trained auditor who practices active listening can significantly improve on that percentage. But the fact is, sometimes we just don’t understand what the other person is trying to say, or the other person doesn’t understand us. Sometimes we think we have nonconformity, but we really don’t.

Rule 7

Don’t go looking for nits. Don’t write up nits. What’s a nit? A nit is any finding that is administrative in nature and could never have any real impact on the performance of the management system. Examples of nits are obvious typographical errors, blank fields not marked “N/A” for “not applicable” when there is no requirement or practical reason to do so, and administrative oversights that are obvious and easily correctable.

Since nits are sometimes violations of requirements, even if trivial, how does an auditor avoid writing them up? The short answer is, don’t go looking for them. Focus on significant requirements, problem areas and performance. Do not focus on, or even look for nits.

Rule 8

Provide sufficient background information in your write-ups to allow the auditee to understand both what was found and what the requirement is. Auditors must always remember who they are writing the nonconformance report for.

It is not for the audit program manager and not for the other auditors. It is for the auditee manager or process owner who will have to take corrective action. The manager or owner might not have been present when the deficiency was found. This means the write-up must be clear and directly traceable to the requirement that was violated. The description of the deficiency must leave no doubt as to what the problem was or why it is considered a violation.

Rule 9

When citing areas of strength, be specific. Shouldn’t the auditor give credit where credit is due? Yes, the auditor should always note superior performance, especially when it represents what is a truly best practice. But the rule for doing so is this: Be specific. When giving praise, it is critical that you pinpoint the specific practices that are praiseworthy. Rarely will an auditor have sufficient time to completely and in great depth evaluate an entire system or process to the point of being able to say the whole thing is really great. Instead, indicate exactly what you found to be superior. Maybe it was the control of electronic documentation or the methods used to communicate changes to document users. Do not make general statements.

Results: Practicing these 9 simple rules, or guidelines, will help you achieve more effective and efficient audits, while helping to provide a more positive image to all those involved.

Very useful artical, it added alot….